[by John Robert Marlow]

Is your book a movie? Should it be? How do you get from here to there—and what’s in it for you? Fasten your seatbelt, and let’s rip through this…

THE AWFUL TRUTH

Let’s face it: being an author is a noble profession, but reaching the financial pinnacle of our chosen profession requires more than the ability to put brilliant words on paper.

Consider Forbes magazine’s 2015 listing of the top ten highest-earning authors: James Patterson, John Green, Veronica Roth, Danielle Steele, Jeff Kinney, J.K. Rowling, Stephen King… Aside from achieving national or international bestseller status, all have one thing in common: heavy film involvement.

Rowling has 8 movies out, with another releasing soon; Green has two movies out, and almost his entire body of published work is in the process of being adapted; King boasts more than 80 film adaptations; Steele more than 20 (television); Roth has 3 movies out and a 4th releasing for television, and so on.

While one could argue that films are simply based on books that are already massive bestsellers, this fails to account for the many bestsellers that have not been made into movies, even when written by some of the same authors whose other books have been filmed (and quite successfully at that).

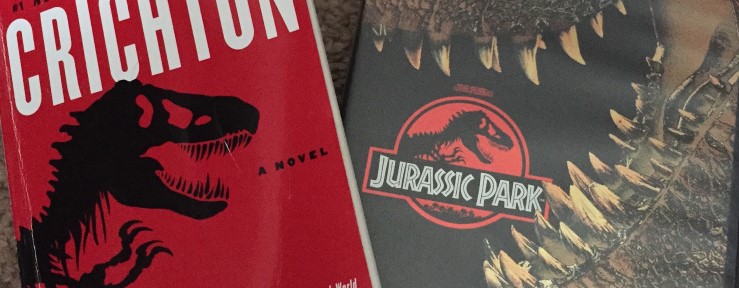

Jurassic Park, one of the most successful book to film adaptations of all time.

Michael Crichton is a perfect example of this: nearly twenty of his works have been adapted to film, his ER TV series is one of biggest ever, and his Jurassic Park adaptations are some of the highest-grossing films of all time. At the time of writing, the first movie of the series, released in 1993, is still the 24th highest-grossing film of all time. The movie rights were purchased before the book had even reached publication. Nevertheless, two of his most recent works, Prey and State of Fear, have yet to be filmed, and it seems likely they never will be. In total, 13 of his novels have been made into films.

Then too, there are those novels and short stories whose performance is poor or middling or genre-specific, which gain widespread recognition only after the film adaptations are released. Bladerunner, Total Recall, and Minority Report were all based on short stories in the science fiction genre. All were written by Philip K. Dick, whose work was – before the movies – largely unknown to the general public. Two of these films, Minority Report and Total Recall, are among the top 300 highest-grossing films in the world.

So while it may be true that Hollywood likes to base movies on existing bestsellers, it’s also obvious that something more is going on here—and equally obvious that if you can make your work appealing to Hollywood, the truth may not be so awful at all. At least not for you. And so the most important question for the novelist may be this:

Why are some books made into movies, and others not—and what can I do to make my book more attractive to Hollywood?

Like publishers, film studios and the companies they deal with look for a good story, well told with interesting characters, properly formatted. But because of the unique demands imposed by filmmaking and marketing considerations, they look for other things as well.

Some of these things simply don’t matter to publishers—making it perfectly possible to have a great book with little film appeal. (Keep in mind, though, that this can be remedied, even if your book has already been published.)

This is what a studio or production company wants to see:

1. A CONCEPT THAT CAN BE COMMUNICATED IN ONE TO THREE SENTENCES

Film agents and studio execs are among the busiest people on the planet. They need to get ideas across to other busy people—and quickly!

If this cannot be done, it suggests that the story is not sharply focused, and that conveying the concept to its potential audience in a 30-second trailer is going to be a problem.

The allure of concept is so strong that screenwriter Joe Eszterhas (who, it must be mentioned, had many previous script sales to his credit) once sold a pitch written on a napkin for $4 million. How many words can you fit on a napkin?

2. STRONG VISUAL POTENTIAL

A novel can go anywhere, even inside the characters’ heads. And it can stay there for 300 pages. Film is a visual medium, and interesting things must pass before the camera.

When not carefully adapted, introspective books make lousy movies. Or, as Groucho Marx once said: “Outside of a dog, a book is man’s best friend. Inside of a dog, it’s too dark to read.”

3. A TWO-HOUR LIMIT

If a story cannot be told in two hours or less (120 script pages), it may be too costly to shoot.

Film is an extraordinarily expensive medium, and when you’re footing a bill that could run a million dollars per minute of screen time, you don’t want to hear that some rookie screenwriter thinks his story should run long. Seasoned veterans with proven track records warrant exceptions; newcomers do not.

4. A RELATABLE HERO

Meaning someone a large segment of the population can relate to, root for, sympathize or empathize with. If moviegoers aren’t likely to care about what happens to your hero, Hollywood doesn’t care about your story. There’s simply too much money at stake to take that kind of chance.

Case in point: the original Pretty Woman script-then titled $3,000-portrayed Vivian as a crack addict and Edward as a cold-blooded type who picks up hookers when his girlfriend’s not around. In the end, Vivian tells him to go to hell, and he drives off.

This was changed, over writer J.F. Lawton’s vigorous objections, to the hugely successful story we now know—in which, of course, Vivian and Edward are much nicer folks, and wind up together. It’s the 76th highest-grossing film of all time.

An assortment of books that have all been successfully adapted for the screen

5. A THREE-ACT STRUCTURE

The overwhelming majority of commercially successful films are “classically structured” into three acts. Even those with additional acts (Star Wars, for example) have three major acts, with the others falling within those.

Generally speaking, non-classically structured films are the province of independent and art house films, in which studios have little interest. The few exceptions typically come from filmmakers who built their reputations on classically-structured films, and then branched out.

6. A REASONABLE BUDGET

In the book world, all scenes are in some sense created equal. The publisher’s cost is the same, whether your characters are sitting down to tea or blowing up a planet.

This is not true of film, where shooting two characters sipping tea might cost $200,000, and filming a major battle sequence could run $10 million. If the story seems prohibitively expensive to film, it will not become a movie unless someone very powerful pushes the project very hard—and even then, there are limits.

7. LOW FAT

Because of time and budgetary restrictions, there’s little or no room for anything that is not absolutely essential to the story. Novelists can spend ten pages describing a room and its furnishings; a screenwriter might do this in a sentence, and going on for more than a paragraph will mark him/her as an amateur.

When lensing two folks having tea can cost a quarter-million dollars, you have to ask yourself just how crucial that tea-sipping scene really is.

8. SEQUEL POTENTIAL

Can a film based on your book be sequeled and prequeled? If so, that’s a big point in your favor. If the first movie hits, it’s a safer financial bet to release a sequel to your film than it is to risk vast sums on something new (and, therefore, untested in the marketplace).

This is not absolutely essential (look at Titanic), but highly desired—to the point where a 300 sequel is now moving forward.

9. “FOUR QUADRANT” APPEAL

In tough economic times, studios look to broaden their audience as much as possible. One way to do this is to base films on already successful properties with built-in audiences (books, graphic novels, video games, toys, other movies). Consider the newest addition to the Star Wars franchise, currently the #1 highest grossing movie of all time.

Another is to make movies that appeal to a larger demographic. The moviegoing audience is composed of four large sections, or quadrants:

- Young Male

- Young Female

- Older Male

- Older Female

The greater the number of quadrants your project appeals to, the better. Four-quadrant appeal is the primary reason for the huge success of animated films—and of Titanic, the biggest-grossing film of all time.

If your story appeals to everyone it’s hard (though still possible) to go wrong. Four-quadrant appeal is not a strict necessity (the more people you pull from one quadrant, the fewer you need to pull from others)—but it’s nice to have.

10. MERCHANDISING POTENTIAL

Film studios make more money from film-related merchandising than they do from the films themselves. A lot more. And while films with low or no merchandising potential continue to be made, the tidal wave is moving the other way, favoring projects with strong merchandising potential.

Film studios make more money from film-related merchandising than they do from the films themselves. A lot more. And while films with low or no merchandising potential continue to be made, the tidal wave is moving the other way, favoring projects with strong merchandising potential.

Even so, this isn’t necessarily something you should alter your novel’s storyline to accommodate; studios are quite adept at wringing merchandising dollars from their films.

Generally speaking, big-budget action and animation films are merchandising bonanzas, while dramas, thrillers, and comedies have considerably less merchandising appeal.

Obviously, this hasn’t kept studios from making dramas, thrillers, and comedies-which are less expensive to film and therefore don’t require the kind of Herculean merchandising blitz needed to keep a marketing juggernaut like the Batman franchise raking in the billions.

If you can make your story meet these basic requirements (an easy statement to make, but not so easy to accomplish), you’re well on your way to successful Movie material.

Don’t miss Part Two of this blog post, which addresses how to implement what Hollywood wants and turn your book into a successful screenplay, and what you can expect if your screenplay sells! And please don’t hesitate to drop me a line if we can help with an adaptation project you’re considering.

Article copyright © by John Robert Marlow – All rights reserved.