There are three important elements of a novel. The story is only one of them. The other two are about connecting readers to that story: the cover, and the title.

Just as in fashion, book titles have trends.

Titles are a contentious subject for fiction writers; most publishing contracts have a clause stipulating that the author’s wishes will be considered, but the publisher has ultimate authority over what the book will be called. Unless you’re a mega best-seller with a lot of clout, chances are your agent, editor, or the marketing department will make the final decision on the title. Sometimes the author gets it right the first time (and choosing a good title is a topic for another blog post) but too many books now are victims of obvious marketing-speak.

One of these book title trends has taken over literary and women’s fiction: wives, daughters, and sisters.

As an example of how far this has gone, here’s an assortment of recent book titles (most within the past five years) that include this element:

The 19th Wife

A Reliable Wife

The Paris Wife

American Wife

The Tiger’s Wife

The Time Traveler’s Wife

The Shoemaker’s Wife

The Apothecary’s Daughter

The Heretic’s Daughter

The Memory Keeper’s Daughter

The Baker’s Daughter

The Hangman’s Daughter

The Hummingbird’s Daughter

Sister: A Novel

Sisters

The Weird Sisters

The Good Sister

My Sister’s Keeper

This is no commentary on the quality of these books or their authors—I’ve read and enjoyed many on the list, and a few are downright wonderful—but if this continues, we’ll soon be reading “The Policeman’s Female Cousin Twice-Removed.”

So why so many wives?

Is it because society places women relative to their familial or spousal relationships? We don’t have many titles like “The Violin Player’s Husband.” Male title characters are perhaps expected to stand on their own without the possessive apostrophe to define them. Is it a commentary on the subverted power of the female, especially in books like The Heretic’s Daughter or American Wife?

Sociology aside, I suspect the real reason is more prosaic. These kinds of titles on these kinds of books must sell better. That one simple gendered word daughter, or wife, or sister, or mother, tells a female reader that the book has something to which she will relate. And women are big readers and book-buyers. At Goodreads, the book social networking site, 70% of members are female.

Then there’s the young adult fiction market, which has been unduly influenced by the wild success of the Twilight series.

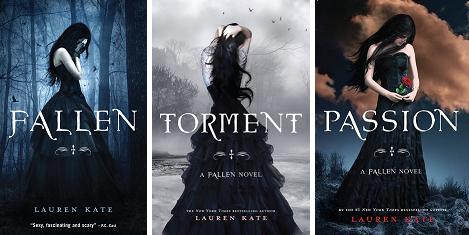

I suspect quite a few of the marketing folks at publishing houses might be secret Twilight fans, and they certainly envy its sales numbers. The proof is in the attempt to capture that same moody, paranormal vibe in YA titles. Most of them are one word, or at most two words, and taken on their own are not particularly offensive. It’s just when you see them lined up on a bookshelf, the whole thing starts to become silly.

Like this.

Evermore

Evernight

Crescendo

Hush, Hush

Prized

Shiver

Linger

Wings

Fallen

Torment

Fade

Wake

Gone

Need

Captivate

Hourglass

Burned

Fire

Ruined

Sleepless

Tithe

Wondrous Strange

Wicked Lovely

Matched

Shadowland

Blue Moon

The list goes on, but I’ll end with Blue Moon because it’s a fine place to stop when the book title is the same as a popular beer.

Most of these are lovely words. A fair few of these books are well-written and entertaining (Wings I particularly enjoyed, and it was the first book I ever read on my new Kindle back in 2011). I can see why the single word might be used for a title—for some books, it’s the only thing that fits. But for a reader looking for a standout YA novel, the over-use of this trend only makes it frustrating and confusing to distinguish truly original stories from the copycats.

As both a writer and a reader, I’d love to see more titles that are both evocative and unique.

Some great examples in YA are The Hunger Games and Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children. In mainstream and women’s fiction, titles like Room and The Help and Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet could easily have fallen victim to relationship-titles (The Basement Wife, The Sisterhood of Domestic Workers, The Immigrant’s Daughter, anyone?) but didn’t, and thank goodness.

We’re told to avoid clichés in our writing, and the same should go for titles. After all, we only have about ten seconds to capture a reader. The title shouldn’t make a potential book-buyer say, “That sounds familiar … I think I’ve already read it.”

Looking for guidance or feedback on your manuscript? We have editors who specialize in everything from plot architecture to character development, world-building to dialogue that sparkles. We can even help you come up with a killer title ;) Please contact Ross Browne at the Tucson office for more information.